What Do We Need to Know about Rights?

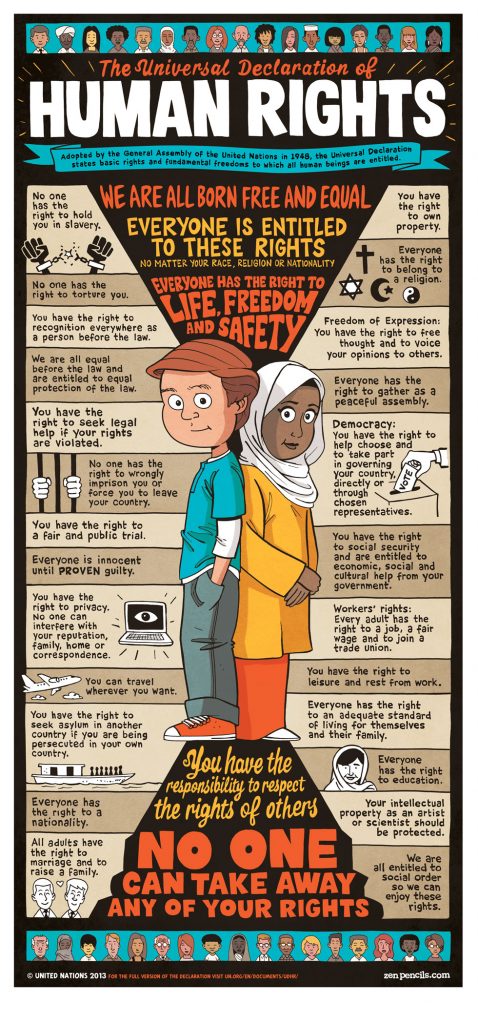

Today as I am writing these lines it is the 10th of December, the International Day for Human Rights. We remember the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the first international regulation – established by the United Nations – from which any human being should benefit.

Two days ago I held a presentation for students who want to become teachers. I asked them what they know about rights and I learned that they know almost nothing. I was 12 years old when I fell in love with a rock oratory of a Hungarian band (Illés), entitled Human Rights. As a high school student, I used to write poems, and I wrote one against the system of apartheid in Rhodezia (today Zimbabwe). I felt that I had to be sympathetic towards those who were suffering. In my college years I received a booklet, which fitted in the palm of my hands, so it was easy to hide if necessary. It was called the Universal Declaration of Human Rights… we were still under communism, and with this in my hands I could easily get in trouble. In that period, the bare mention of human rights represented a rebellion against the system. But I was interested to know what the dictatorship stole from me.

Why doesn’t Romania’s youth want to know their rights? Why doesn’t institutionalized education offer sufficient information about rights? We no longer live in a dictatorship, but this doesn’t mean that we always benefit of the full use of our rights. In any country it is possible for human rights to suffer. According to the statistics of the European Court of Human Rights, Romania is among those European countries where rights are violated more frequently. But if we do not know our rights, we cannot claim them.

Some examples of rights that are violated on a daily basis:

- The vast majority of public transport is inaccessible to people with locomotive disabilities;

- Many elderly people lose their work because employers want younger employees, considered to be more energetic, more open-minded;

- Children in rural areas do not benefit from quality education;

- Many Roma children learn in segregated classes, separated from their non-Roma peers;

- Women have a lower income than men.

What do we need to know about these rights?

Rights are universal. All human beings should benefit from them. They do not depend on culture, such as language or religion.

Some of these rights are inalienable, which means that they cannot be restricted under any circumstances. In this category we can include, for example, the right to human treatment. Other rights may be limited, such as the right to freedom. A person who has committed an offence may be sentenced by an independent court to imprisonment.

There isn’t a correlation between rights and obligations. Human rights are applicable to people who do not have obligations (such as children) or who do not comply with their obligations (those who have committed offences cannot be punished through inhumane treatments).

The compliance of rights is an international obligation and not an internal problem of the states. For this purpose, there are the international treaties, which serve to protect against abuses of state authorities. The citizens of Romania, which is a state member of the Council of Europe, can apply to the European Court of Human Rights in case the national courts do not respect the human rights.

But above all, in order to promote human rights, one must feel solidarity with those who are more exposed to abuse than others. Although the first article of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirms that all human beings are born equal in rights, in fact the situation is different. Some of us are lucky to be born into a family with no problems; others are born into families where even the everyday bread is hard to find. To say that we are equal means to disregard reality. To be born equal is still a desideratum. If during our childhood our parents’ dilemma is whether to have us take violin classes or piano classes, then we have a life much more different from those whose parents are thinking about sending their children to beg or reap corn. The moral obligation of the most fortunate is to focus on those who are not in this situation. When I was in middle school I was among the best in learning, so I was the teacher’s pet. When a teacher hit a classmate for not doing his homework, I believed that it was my obligation to stand up and tell the teachers to stop doing that. Because I wouldn’t get in trouble for this attitude.

Do you understand now why the young people in Romania don’t want to know their rights?

Do you understand why institutionalized education does not provide sufficient information about rights?

Maybe you will find the answers.

By Istvan Haller

I was born in 1962, I studied geology in college and I had worked as a geologist until 1990, when I became a journalist. Since 1993 I’ve led the Human Rights Office within the PRO EUROPA League. In this capacity, I attended a number of conferences, including the ones of the UN, OSCE, and the Council of Europe, and I wrote various articles and studies, especially regarding the Roma population and discrimination. Since 2007 I have been a member of the National Council for Combating Discrimination. I graduated from law school and obtained a Ph.D. in sociology. As a trainer, I hold presentations on discrimination to judges, prosecutors, policemen and other categories of civil servants.